The Low-Bar Back Squat & Weightlifting

As the new standard of back squatting within the CrossFit community, Mark Rippetoe’s low-bar back squat is a regular focus of questions in regard to its suitability for Olympic weightlifting. Rippetoe has made clear in the new edition of Starting Strength and elsewhere his belief that the low-bar back squat is more appropriate for weightlifters than the traditional high-bar Olympic back squat. While, as usual, his argument is not without merit, I disagree that the low-bar back squat is appropriate for weightlifters, and wish to collect all of my arguments into a single place.

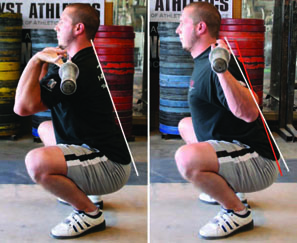

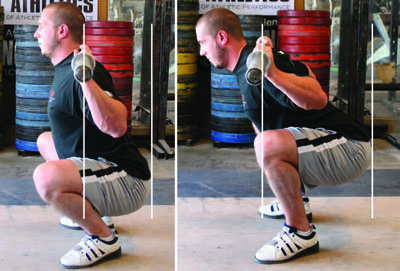

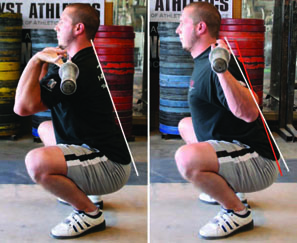

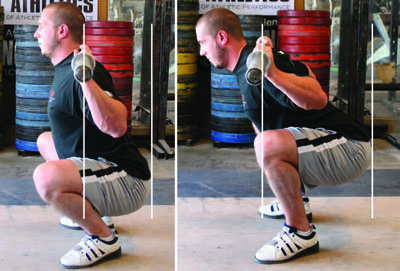

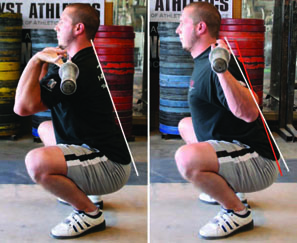

The low-bar back squat has been described in great detail by Rippetoe in both his book Starting Strength and numerous CrossFit Journal articles. In this squat variation, the bottom position of the squat places the crease of the hips just below the top of the knee, the hips relatively far behind the heels, and the torso necessarily inclined forward considerably. The barbell is held just above the origins of the posterior delts to reduce the moment on the hip.

The Olympic squat is defined by the extremely erect torso. This nearly vertical torso position requires the hips be close to the heels and the knees protrude considerably over the toes, and allows the hips to be lowered to the fullest depth anatomically possible.

As its name suggests, application for the Olympic squat is training specifically for the Olympic lifts, while the low-bar back squat is typically appropriate for most other athletic training applications. Rippetoe has made the argument that the low-bar back squat should replace the traditional high-bar Olympic back squat employed by weightlifters. This argument is predicated on two primary notions. First, that because this squat variation allows more weight to be handled, it will be superior in producing strength and consequently improve the lifter’s performance of the snatch and clean & jerk; second, that because the positioning of this squat variation is very similar to the pulling position of the snatch and clean, its performance will improve the pulling ability of the athlete in these two lifts.

In addition to these points, Rippetoe adds that the low-bar back squat is “easier on the lower back,” and comments that because the squat is not actually contested in Olympic weightlifting, its sole purpose is as a strength exercise to improve the snatch and clean & jerk, and that weightlifters already use front squats to improve specific leg strength.

Let’s first establish the uncontested points. That the low-bar back squat will allow more weight to be lifted than a high-bar back squat is true, assuming the two are compared by an athlete with balanced strength (In other words, this is not necessarily true for a weightlifter who may have a relatively weak posterior chain and consequently be capable of squatting more with a high-bar position more reliant on the quads and less demanding of posterior chain strength. For this athlete, it may take many months of training to bring the strength of the low-bar back squat to the level being discussed here.).

The positioning of the low-bar back squat is indeed remarkably similar to the pulling position of the snatch and clean in terms of both back angle and bar positioning relative to the torso, and the strength developed from this squat variation will certainly improve pulling strength for these two lifts. And finally, the squat is in fact not contested in Olympic weightlifting—the only interest is snatching and clean & jerking as much as possible.

Now to the disagreements. First, that the low-bar back squat is “easier on the lower back,” than the high-bar squat is a statement requiring some qualification. By “easier” on the lower back, the implication is less torque is placed on it. However, this is not at all correct. Readers commonly come to the conclusion that the closer the barbell is placed to the lower back, the less torque will be placed on the joints; but this is only true if the angle of the back doesn’t change. The critical point is that the torso is at an entirely different angle in the Olympic squat and that basic comparison of direct distance between bar and joint is inadequate.

Torque is measured perpendicularly to the line of force. That force, in this case, is gravity, and here on Earth, gravity always acts perpendicularly to the ground. This means torque must be measured according to the horizontal distance between the load and the joint in question, irrespective of the angle of the body part connecting the two.

The upright posture of the Olympic squat results in an extremely short horizontal distance between the barbell and the hips and lower back. The low-bar back squat with its smaller torso angle relative to the ground, even with the placement of the bar farther down the back, creates a comparatively huge distance between the bar and the hips and lower back, resulting in far more lower back torque than the Olympic squat.

In response to this, it’s stated that the greater distance between the hip and barbell in the high-bar back squat magnifies any disturbances in position and consequently makes stabilization more difficult. Again, this is true only when the moment on the lower back is similar to that of the low-bar back squat—that is, the horizontal distance between the bar and lower back is the same. Disturbances of that magnitude simply don’t happen with athletes familiar with the Olympic squat and strong in its position. Essentially, this argument assumes an inability by the athlete to perform the movement correctly.

Coach Rippetoe’s contention that the low-bar back squat is more beneficial for weightlifters than the high-bar back squat for reasons of strength development is comprised of four aspects: first, that the squat is not a contested lift in weightlifting and therefore there is no need for it to conform to any technique for reasons other than strength development; two, that weightlifters already use the front squat to improve strength for the clean; three, that because the positioning of the low-bar back squat so well resembles the pulling position of the snatch and clean that it will also develop posterior chain strength applicable to the pulls of these lifts, and this is necessary because weightlifters or their coaches refuse to use deadlifts; and finally, that because the low-bar back squat will allow greater loading than the high-bar back squat, it will develop more strength for the weightlifter.

We’ve already established that the squat is indeed a training exercise and not a contested lift, and consequently that it should be performed in whatever manner produces the best possible gains for the weightlifter. Let’s consider the purposes of the front squat and back squat for the weightlifter. First, the recovery from the clean demands the most leg strength and that being the case we can say that the development of greater leg strength will be most evident in the performance of the clean, although it will of course play an enormous role in all aspects of the classic lifts. The jerk, for example, relies overwhelmingly on quad strength because of the position of the dip and drive—increased posterior chain strength will have little if any effect on the jerk, while increased quad strength and the ability to maintain erect torso positioning under heavy loads will improve the jerk dramatically.

The front squat demands great leg strength, but also has a considerable core stabilization component due to the placement of the bar in front of the spine and the resultant torque. Forward collapse of the spine is possibly responsible for failed front squats as much as inadequate leg drive, if not more. That said, the front squat may be considered as much of a core exercise as a leg exercise.

The Olympic back squat, however, positions the bar behind and in immediate proximity to the spine, greatly reducing the tendency for it to round forward. This is done with very little change in the position of the body, including the angle of the torso. This means the work the legs must perform in the Olympic back squat is nearly identical to the front squat—the difference is the greater security and comfort of the bar position and a considerable reduction in the core stability element. This allows the lifter to squat greater loads than with the front squat while in nearly the same position and consequently elicit greater leg strength gains. While the surplus of weight is not immense, the transferability of the strength development is extremely high—in other words, in terms of applicable leg strength, the Olympic back squat delivers the most.

With the right conditions—i.e. the balanced strength described previously—it’s likely an athlete would be able to squat more with a low-bar conventional back squat than with a high-bar Olympic back squat. This greater loading, Rippetoe argues, makes the low-bar back squat more valuable for the weightlifter both in terms of direct muscle development as well as hormonal response.

All other things being equal, greater loading will always produce better strength gains. But all other things are not equal, and this is a critical point. The extremely upright torso and knees-forward position of the clean greatly limits the ability of the hamstrings to contribute to the movement. This is why the typical weightlifter will display great quad and glute development and comparatively poorly developed hamstrings. This is simply the nature of the squat positions demanded by Olympic weightlifting.

The low-bar back squat allows greater loading quite simply by allowing more of the body to participate in the effort—the difference is much greater hamstring involvement relative to the Olympic squat. In other words, the improved loading is achieved by involving a muscle group that cannot be equally involved in the primary movement we’re trying to strengthen—the clean—and to a lesser extent, the jerk. This also means that at a given load, this increased participation of the hamstrings will reduce the work demanded of the quads relative to the front squat or clean, and consequently reduce their strength development. The loading of the low-bar back squat, then, would need to be dramatically greater than the high-bar Olympic back squat or front squat to produce better strength gains in the quads, the primary muscles at work in the clean and front squat. Whether or not such a dramatic difference is achievable is questionable, and very unlikely without a period of dedicated training with this squat variation.

The next problem we encounter is the disparity in the nature of the movements based largely on the respective bottom positions of the two squat variations. The Olympic squat at the bottom places the lifter with an erect torso, allowing the hips to remain close to the heels and consequently allowing full depth to be reached, resulting in contact over a relatively large area between the hamstrings and calves. The low-bar back squat cannot achieve this depth due to its torso and hip position requirements, and breaking horizontal with the thighs has been established as the lowest position. Quite simply, this means the bottom position of the low-bar back squat must be maintained with constant muscular tension exclusively, while the Olympic squat adds to that tension a solid static structure to support the load—in essence, the spine sites directly on the pelvis, which sits directly on the feet—potential movement of the joints in between is effectively eliminated.

This has implications beyond simply the comfort of maintaining the bottom position for extended periods of time, which, with the exception of occasional pause squats to develop strength for recovering from poorly executed cleans, we don’t want to do. This difference in the structural integrity of the bottom position effects directly and dramatically the bounce effect.

The bounce is the rapid transition at the bottom of the squat, and is absolutely critical for the success of maximal cleans, particularly for lifters with comparatively weak legs. Achieving a bounce is, as Rippetoe has written, possible with the low-bar back squat, but it is strictly limited to the stretch-shortening cycle of the involved muscles. In the context of Olympic weightlifting, the bounce is actually comprised of three aspects: the stretch-shortening cycle of the muscles, the whip of the barbell, and the literal bounce resulting from the collision of the hamstrings on the calves. Neither of these second two aspects are possible with the low-bar back squat, particularly at the loads we’ve decided would be necessary for the variation to be beneficial, and the first is possible to a greater degree with the greater possible speef of the Olympic squat. The collision of the hamstrings and calves cannot of course be possible when the two stop short of meeting each other sufficiently, and the whip of the barbell requires a more abrupt cessation of downward movement than can be achieved in such an unsupported bottom position as is inherent to the low-bar back squat. Similarly, the speed at which the athlete can enter the bottom position of the low-bar back squat is limited relative to the Olympic squat because of the inability to arrest such great magnitudes of force in such an unsupported position. In short, the low-bar back squat removes too much of the necessary bounce and speed elements of the squat for weightlifters.

Finally, Rippetoe’s observation that the position of the low-bar back squat is very similar to the pulling positions of the snatch and clean is wholly astute and accurate. But this alone is inadequately compelling for its use by weightlifters. There is no argument that a low-bar back squat would not allow strength improvement for the pulls of the snatch and clean primarily through strengthening of the posterior chain. However, so will snatch and clean deadlifts and snatch and clean pulls. More importantly, deadlifts and pulls are far more applicable since they not only involve the positional loading but the crucial activity of the arms and the navigation of the bar up the legs, and, with pulls, the all-important component of speed. There is no sense in eliminating these elements if doing so will not somehow provide benefits elsewhere. To say that weightlifters need to employ the low-bar back squat because they don’t employ the deadlift makes little sense—if we’re going to encourage a change, it’s far more logical and reasonable to encourage the use of deadlifts rather than dramatically change the style of squat. Further, many weightlifters do in fact perform deadlifts, and those who don’t nearly invariably perform pulls at loads beyond their maximal lifts.

Is the low-bar back squat detrimental to weightlifters? Of course not. In reality, the difference between it and the Olympic back squat for novice weightlifters and CrossFitters may be insignificant because of these individuals’ relatively low strength levels and immature technique. Each individual should choose the squat variation he or she finds delivers the best results. For the reasons above, my encouragement of the use of the Olympic squat increases with an individuals’ weightlifting experience and desire for progress in that specific arena.

The low-bar back squat offers immense benefits for non-weightlifter athletes and those who have popularly become known so obnoxiously as fitness enthusiasts. It should certainly not be discounted by any means, and deserves a place in many individuals’ training.

The low-bar back squat has been described in great detail by Rippetoe in both his book Starting Strength and numerous CrossFit Journal articles. In this squat variation, the bottom position of the squat places the crease of the hips just below the top of the knee, the hips relatively far behind the heels, and the torso necessarily inclined forward considerably. The barbell is held just above the origins of the posterior delts to reduce the moment on the hip.

The Olympic squat is defined by the extremely erect torso. This nearly vertical torso position requires the hips be close to the heels and the knees protrude considerably over the toes, and allows the hips to be lowered to the fullest depth anatomically possible.

As its name suggests, application for the Olympic squat is training specifically for the Olympic lifts, while the low-bar back squat is typically appropriate for most other athletic training applications. Rippetoe has made the argument that the low-bar back squat should replace the traditional high-bar Olympic back squat employed by weightlifters. This argument is predicated on two primary notions. First, that because this squat variation allows more weight to be handled, it will be superior in producing strength and consequently improve the lifter’s performance of the snatch and clean & jerk; second, that because the positioning of this squat variation is very similar to the pulling position of the snatch and clean, its performance will improve the pulling ability of the athlete in these two lifts.

In addition to these points, Rippetoe adds that the low-bar back squat is “easier on the lower back,” and comments that because the squat is not actually contested in Olympic weightlifting, its sole purpose is as a strength exercise to improve the snatch and clean & jerk, and that weightlifters already use front squats to improve specific leg strength.

Let’s first establish the uncontested points. That the low-bar back squat will allow more weight to be lifted than a high-bar back squat is true, assuming the two are compared by an athlete with balanced strength (In other words, this is not necessarily true for a weightlifter who may have a relatively weak posterior chain and consequently be capable of squatting more with a high-bar position more reliant on the quads and less demanding of posterior chain strength. For this athlete, it may take many months of training to bring the strength of the low-bar back squat to the level being discussed here.).

The positioning of the low-bar back squat is indeed remarkably similar to the pulling position of the snatch and clean in terms of both back angle and bar positioning relative to the torso, and the strength developed from this squat variation will certainly improve pulling strength for these two lifts. And finally, the squat is in fact not contested in Olympic weightlifting—the only interest is snatching and clean & jerking as much as possible.

Now to the disagreements. First, that the low-bar back squat is “easier on the lower back,” than the high-bar squat is a statement requiring some qualification. By “easier” on the lower back, the implication is less torque is placed on it. However, this is not at all correct. Readers commonly come to the conclusion that the closer the barbell is placed to the lower back, the less torque will be placed on the joints; but this is only true if the angle of the back doesn’t change. The critical point is that the torso is at an entirely different angle in the Olympic squat and that basic comparison of direct distance between bar and joint is inadequate.

Torque is measured perpendicularly to the line of force. That force, in this case, is gravity, and here on Earth, gravity always acts perpendicularly to the ground. This means torque must be measured according to the horizontal distance between the load and the joint in question, irrespective of the angle of the body part connecting the two.

The upright posture of the Olympic squat results in an extremely short horizontal distance between the barbell and the hips and lower back. The low-bar back squat with its smaller torso angle relative to the ground, even with the placement of the bar farther down the back, creates a comparatively huge distance between the bar and the hips and lower back, resulting in far more lower back torque than the Olympic squat.

In response to this, it’s stated that the greater distance between the hip and barbell in the high-bar back squat magnifies any disturbances in position and consequently makes stabilization more difficult. Again, this is true only when the moment on the lower back is similar to that of the low-bar back squat—that is, the horizontal distance between the bar and lower back is the same. Disturbances of that magnitude simply don’t happen with athletes familiar with the Olympic squat and strong in its position. Essentially, this argument assumes an inability by the athlete to perform the movement correctly.

Coach Rippetoe’s contention that the low-bar back squat is more beneficial for weightlifters than the high-bar back squat for reasons of strength development is comprised of four aspects: first, that the squat is not a contested lift in weightlifting and therefore there is no need for it to conform to any technique for reasons other than strength development; two, that weightlifters already use the front squat to improve strength for the clean; three, that because the positioning of the low-bar back squat so well resembles the pulling position of the snatch and clean that it will also develop posterior chain strength applicable to the pulls of these lifts, and this is necessary because weightlifters or their coaches refuse to use deadlifts; and finally, that because the low-bar back squat will allow greater loading than the high-bar back squat, it will develop more strength for the weightlifter.

We’ve already established that the squat is indeed a training exercise and not a contested lift, and consequently that it should be performed in whatever manner produces the best possible gains for the weightlifter. Let’s consider the purposes of the front squat and back squat for the weightlifter. First, the recovery from the clean demands the most leg strength and that being the case we can say that the development of greater leg strength will be most evident in the performance of the clean, although it will of course play an enormous role in all aspects of the classic lifts. The jerk, for example, relies overwhelmingly on quad strength because of the position of the dip and drive—increased posterior chain strength will have little if any effect on the jerk, while increased quad strength and the ability to maintain erect torso positioning under heavy loads will improve the jerk dramatically.

The front squat demands great leg strength, but also has a considerable core stabilization component due to the placement of the bar in front of the spine and the resultant torque. Forward collapse of the spine is possibly responsible for failed front squats as much as inadequate leg drive, if not more. That said, the front squat may be considered as much of a core exercise as a leg exercise.

The Olympic back squat, however, positions the bar behind and in immediate proximity to the spine, greatly reducing the tendency for it to round forward. This is done with very little change in the position of the body, including the angle of the torso. This means the work the legs must perform in the Olympic back squat is nearly identical to the front squat—the difference is the greater security and comfort of the bar position and a considerable reduction in the core stability element. This allows the lifter to squat greater loads than with the front squat while in nearly the same position and consequently elicit greater leg strength gains. While the surplus of weight is not immense, the transferability of the strength development is extremely high—in other words, in terms of applicable leg strength, the Olympic back squat delivers the most.

With the right conditions—i.e. the balanced strength described previously—it’s likely an athlete would be able to squat more with a low-bar conventional back squat than with a high-bar Olympic back squat. This greater loading, Rippetoe argues, makes the low-bar back squat more valuable for the weightlifter both in terms of direct muscle development as well as hormonal response.

All other things being equal, greater loading will always produce better strength gains. But all other things are not equal, and this is a critical point. The extremely upright torso and knees-forward position of the clean greatly limits the ability of the hamstrings to contribute to the movement. This is why the typical weightlifter will display great quad and glute development and comparatively poorly developed hamstrings. This is simply the nature of the squat positions demanded by Olympic weightlifting.

The low-bar back squat allows greater loading quite simply by allowing more of the body to participate in the effort—the difference is much greater hamstring involvement relative to the Olympic squat. In other words, the improved loading is achieved by involving a muscle group that cannot be equally involved in the primary movement we’re trying to strengthen—the clean—and to a lesser extent, the jerk. This also means that at a given load, this increased participation of the hamstrings will reduce the work demanded of the quads relative to the front squat or clean, and consequently reduce their strength development. The loading of the low-bar back squat, then, would need to be dramatically greater than the high-bar Olympic back squat or front squat to produce better strength gains in the quads, the primary muscles at work in the clean and front squat. Whether or not such a dramatic difference is achievable is questionable, and very unlikely without a period of dedicated training with this squat variation.

The next problem we encounter is the disparity in the nature of the movements based largely on the respective bottom positions of the two squat variations. The Olympic squat at the bottom places the lifter with an erect torso, allowing the hips to remain close to the heels and consequently allowing full depth to be reached, resulting in contact over a relatively large area between the hamstrings and calves. The low-bar back squat cannot achieve this depth due to its torso and hip position requirements, and breaking horizontal with the thighs has been established as the lowest position. Quite simply, this means the bottom position of the low-bar back squat must be maintained with constant muscular tension exclusively, while the Olympic squat adds to that tension a solid static structure to support the load—in essence, the spine sites directly on the pelvis, which sits directly on the feet—potential movement of the joints in between is effectively eliminated.

This has implications beyond simply the comfort of maintaining the bottom position for extended periods of time, which, with the exception of occasional pause squats to develop strength for recovering from poorly executed cleans, we don’t want to do. This difference in the structural integrity of the bottom position effects directly and dramatically the bounce effect.

The bounce is the rapid transition at the bottom of the squat, and is absolutely critical for the success of maximal cleans, particularly for lifters with comparatively weak legs. Achieving a bounce is, as Rippetoe has written, possible with the low-bar back squat, but it is strictly limited to the stretch-shortening cycle of the involved muscles. In the context of Olympic weightlifting, the bounce is actually comprised of three aspects: the stretch-shortening cycle of the muscles, the whip of the barbell, and the literal bounce resulting from the collision of the hamstrings on the calves. Neither of these second two aspects are possible with the low-bar back squat, particularly at the loads we’ve decided would be necessary for the variation to be beneficial, and the first is possible to a greater degree with the greater possible speef of the Olympic squat. The collision of the hamstrings and calves cannot of course be possible when the two stop short of meeting each other sufficiently, and the whip of the barbell requires a more abrupt cessation of downward movement than can be achieved in such an unsupported bottom position as is inherent to the low-bar back squat. Similarly, the speed at which the athlete can enter the bottom position of the low-bar back squat is limited relative to the Olympic squat because of the inability to arrest such great magnitudes of force in such an unsupported position. In short, the low-bar back squat removes too much of the necessary bounce and speed elements of the squat for weightlifters.

Finally, Rippetoe’s observation that the position of the low-bar back squat is very similar to the pulling positions of the snatch and clean is wholly astute and accurate. But this alone is inadequately compelling for its use by weightlifters. There is no argument that a low-bar back squat would not allow strength improvement for the pulls of the snatch and clean primarily through strengthening of the posterior chain. However, so will snatch and clean deadlifts and snatch and clean pulls. More importantly, deadlifts and pulls are far more applicable since they not only involve the positional loading but the crucial activity of the arms and the navigation of the bar up the legs, and, with pulls, the all-important component of speed. There is no sense in eliminating these elements if doing so will not somehow provide benefits elsewhere. To say that weightlifters need to employ the low-bar back squat because they don’t employ the deadlift makes little sense—if we’re going to encourage a change, it’s far more logical and reasonable to encourage the use of deadlifts rather than dramatically change the style of squat. Further, many weightlifters do in fact perform deadlifts, and those who don’t nearly invariably perform pulls at loads beyond their maximal lifts.

Is the low-bar back squat detrimental to weightlifters? Of course not. In reality, the difference between it and the Olympic back squat for novice weightlifters and CrossFitters may be insignificant because of these individuals’ relatively low strength levels and immature technique. Each individual should choose the squat variation he or she finds delivers the best results. For the reasons above, my encouragement of the use of the Olympic squat increases with an individuals’ weightlifting experience and desire for progress in that specific arena.

The low-bar back squat offers immense benefits for non-weightlifter athletes and those who have popularly become known so obnoxiously as fitness enthusiasts. It should certainly not be discounted by any means, and deserves a place in many individuals’ training.

| Greg Everett is the owner of Catalyst Athletics, publisher of The Performance Menu Journal and author of Olympic Weightlifting: A Complete Guide for Athletes & Coaches, Olympic Weightlifting for Sports, and The Portable Greg Everett, and is the writer, director, producer, editor, etc of the independent documentary American Weightlifting. Follow him on Facebook here. |

Search Articles

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date

Article Categories

Sort by Author

Sort by Issue & Date